Is web scraping legal?

Web scraping is generally legal if you scrape data that is publicly available on the internet. However, some kinds of data are protected by terms of service or national and even international regulations, so take great care when scraping data behind a login, personal data, intellectual property, or confidential data.

Contrary to popular belief, there’s nothing shady or illicit about web scraping itself. That does not mean that any kind of web scraping is legal. Like all human activity, it needs to remain within certain boundaries. In web scraping, the most important boundaries are personal data and intellectual property regulations, but other factors, such as the website’s terms of service, can play a role as well.

If you want to learn more about the legality of web scraping, read on. We will cover the most important areas of confusion one by one and give you some useful tips to keep your scrapers compliant and ethical.

Need to learn more about web scraping? You'll find our web scraping for beginners course on Apify Academy a great place to start. It's designed to take you from an absolute beginner to a successful web scraper developer.

We are lawyers, but we are not your lawyers. Even though we want to help as much as we can, we do not know the details of your project. For professional legal advice, please talk to a certified lawyer in your country.

What you’ll learn:

- Common misconceptions around web scraping.

- The most important things to keep your scrapers ethical.

- What’s personal data and how to identify it.

- How copyright influences scraping.

- How websites prevent scraping with their Terms of Use.

- What is the CFAA and how it relates to web scraping.

Deploy any scraper to the cloud with Apify

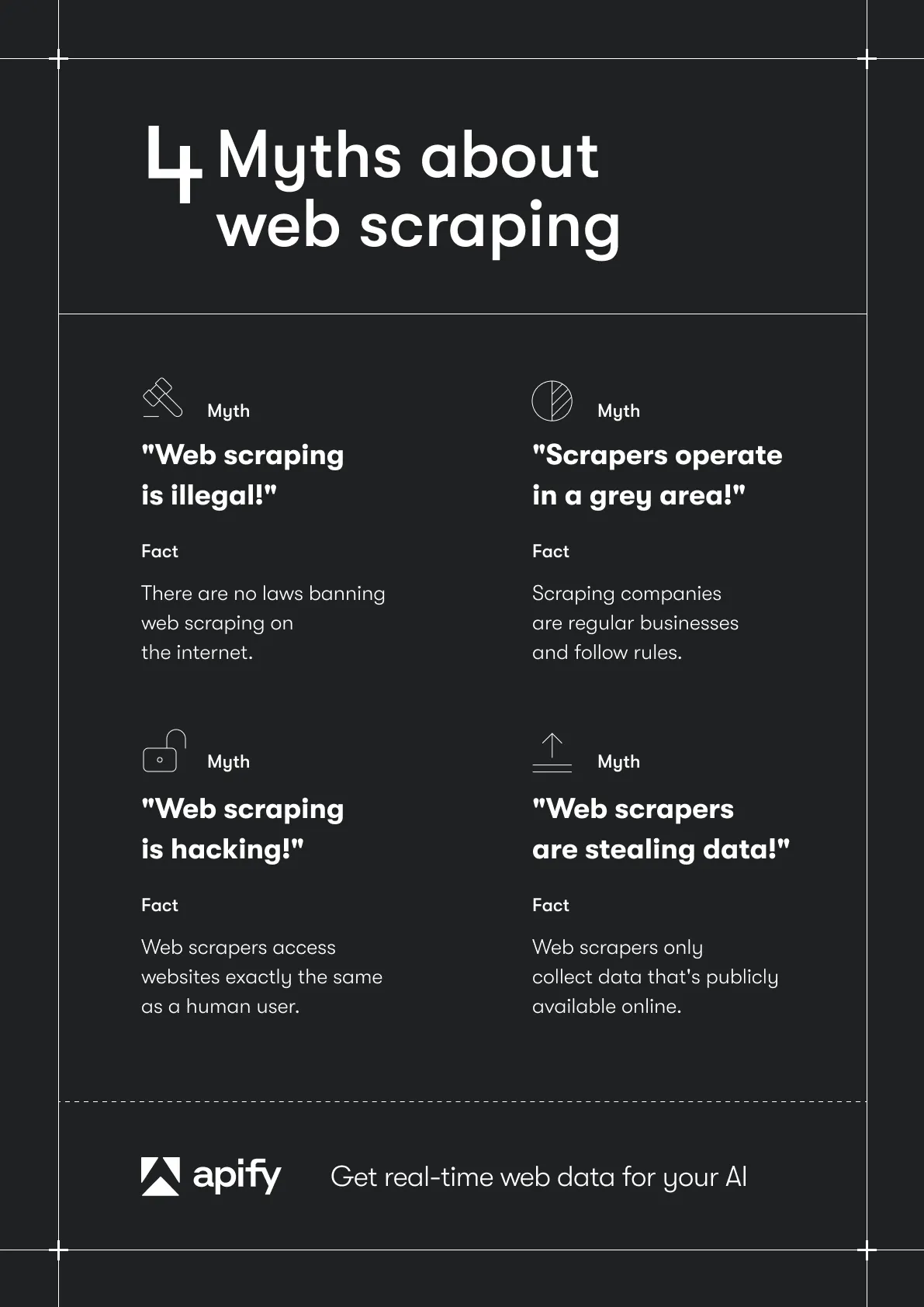

4 myths about web scraping

Before we start, let’s clear up a few fallacies. We sometimes hear that “web scrapers operate in a grey area of law”. Or that “web scraping is illegal, but nobody enforces the illegality, because it’s difficult”. Sometimes even that “web scraping is hacking” or “web scrapers are stealing our data”. We've heard this from clients, friends, interviewees, and other companies. The thing is, none of that is true.

Myth 1: Web scraping is illegal

It’s all a matter of what you scrape and how you scrape it. It’s quite similar to taking pictures with your phone. In most cases, it is perfectly legal, but taking pictures of an army base or confidential documents might get you in trouble. Web scraping is the same. There is no general law or rule banning web scraping. But that does not mean you can scrape everything.

Myth 2: Web scrapers operate in a grey area of law

Not at all. Legitimate web scraping companies are regular businesses and follow the same set of rules and regulations everyone else needs to follow to do their respective business. Web scraping is not heavily regulated, that’s true. But that does not imply anything illicit. Quite the contrary.

Myth 3: Web scraping is hacking

Even though the word hacking has many interpretations, it’s mostly used to describe access to a computer system through unauthorized means, exploiting the system. Web scrapers access websites exactly the same way as a legitimate human user would. They do not exploit vulnerabilities and they access only data that’s publicly available.

Myth 4: Web scrapers are stealing data

Web scrapers only collect data that’s publicly available on the internet. Can public data be stolen? Imagine you see a nice shirt in a store, so you pull out your phone and take a note of the brand and price. Would you think you stole the information? No, you wouldn’t. Yes, some kinds of data are protected by various regulations, and we’ll cover that later, but other than that, there’s nothing to worry about when collecting facts like prices, locations, or review stars.

What about web scraping around the world?

Is web scraping legal in the US?

The US courts have consistently upheld the legality of web scraping of publicly available data from the internet if conducted appropriately. However, you should be careful when scraping data behind a login, personal data, intellectual property, or confidential data. Relevant regulations in the US include the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), Copyright Law, and various privacy laws such as California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), Colorado Privacy Act (CPA), or Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA).

Is web scraping legal in Europe?

Scraping publicly available data from the internet is generally legal in the EU. Just like in the US, you should be extra cautious when scraping data behind a login, personal data, intellectual property, or confidential data. Also, make sure your scraping doesn't violate any EU or national regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Database Directive, or the Digital Single Market Directive.

Is web scraping legal in the UK?

You can scrape publicly available data from the internet in the UK. However, just like in the US or the EU, you should consider whether your conduct doesn't violate any laws, especially when scraping data behind a login, personal data, intellectual property, or confidential data. The most important regulations for web scrapers include the Data Protection Act, the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, and the Computer Misuse Act.

How to make ethical scrapers

Even though most of the bad things you read about scraping are not true, you still need to be careful about it. Frankly, you should be careful when doing business of any kind. And web scraping is no exception. There are certain kinds of data you should not scrape before talking to your lawyer, and the most important kind is personal data, with intellectual property in close second.

It does not mean that web scraping is dangerous. There are rules, yes, but you can use empathy to tell whether your scraping will be ethical and lawful or not. Amber Zamora proposes a list of features that an ethical scraper should have:

- The data scraper acts as a good citizen of the web, and does not seek to overburden the targeted website;

- The information copied was publicly available and not behind a password authentication barrier;

- The information copied was primarily factual in nature, and the taking did not infringe on the rights — including copyrights — of another; and

- The information was used to create a transformative product and was not used to steal market share from the target website by luring away users or creating a substantially similar product.

If you follow these guidelines, you can be confident that your scrapers will be ethical.

This article provides guidelines for scraping ethically as a business. If you're scraping for your personal project or for academic research, it will be a bit easier for you, but we will not cover those exceptions here.

Think twice before scraping personal data

Not too long ago, few people worried about personal data. At the time, there were few specific regulations governing personal data, and information like names, birthdates, and shopping preferences was often collected and used with little oversight or restriction. This is no longer the case, especially in the European Union (EU), and other jurisdictions, notably California and other US state legislation, Brazil with the Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados (LGPD), or Canada with the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). If you scrape personal data, you should definitely learn about the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), as this significant piece of legislation has broad applicability and it has been a foundation for many other privacy laws worldwide.

Since the regulations are different around the world, you need to think carefully about where the data comes from and whose data you scrape. In some countries, it might be completely fine, while in other places you should avoid scraping personal data completely. If you want to learn more, here is a nice overview of the current evolution of global privacy laws.

How do you know whether to apply GDPR, CCPA, or some other regulation? This is a simplification, but if you're from the EU, you do business in the EU, or the people whose data you want are in the EU, GDPR will apply. It is one of the most far-reaching privacy laws in the world. On the other hand, CCPA applies only to for-profit businesses that collect personal data from California residents, and if they meet certain thresholds. We use it for comparison and because it's pioneering legislation in the United States. Wherever you are, you should always check your own country's privacy laws.

What is personal data (information) anyway?

GDPR defines personal data as follows: “Personal data means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person.” That's a bit hard to read, but gives us an idea of just how broad the definition is. Almost anything can be personal data if it relates to a specific human being. The CCPA definition is fairly similar, but it calls it personal information. For simplicity, we will use only the term personal data.

To illustrate the broadness of the definition, let’s look at some examples of personal data:

- Official data about a person

- name, surname

- date of birth

- address

- social security number, passport number, national ID number

- employment information

- Contact details

- phone number

- email address

- IP address

- Facebook, X/Twitter, and other network handles

- Data often collected by applications

- location either by address or GPS

- shopping preferences

- behavioral data

- Video + audio recordings of people and biometric data

- Special categories of personal data

- sex, gender, and sexual orientation

- racial or ethnic origin

- religious beliefs

- political opinions

- medical records

As you can see, pretty much any information about a human being constitutes personal data. Don't forget that this is not an exhaustive list. When in doubt, read the definition again and try to decide whether your piece of information fits it or not.

Publicly available personal data

A large part of the web scraping community lives under the wrong impression that only private personal data is protected, whatever that means, and that scraping personal data from publicly available sources - websites - is totally fine. Well, it depends.

Under GDPR, all personal data is protected, and it does not matter at all where the data comes from. A company in the EU was fined a pretty large sum for scraping publicly available personal data from the Polish business register. A court later overturned the fine, but explicitly upheld the ban on scraping publicly available personal data.

Under CCPA, information made available by the government, such as business register data, is considered "publicly available" and therefore not protected. In the US, there's an important case dealing with the scraping of publicly available data from social networks: HiQ vs. LinkedIn. The court's latest decision supports the idea of scraping personal information that was made public by the person.

In 2023, the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) came into effect, broadening the CCPA definition of publicly available information. Personal data that was previously made public by the subject is no longer protected, including the user's right to opt out of the sale of such information. This may have effectively allowed the scraping of personal data from websites where people make their personal data freely available, like LinkedIn or Facebook, but only in California. Other US states, such as Colorado and Virginia, have introduced similar legislation, and we might expect even more US states to take inspiration from the CCPA and CPRA in their own privacy legislation.

How to scrape personal data ethically

Before you start with the legal analysis, use empathy. Do you think the person whose data you're scraping would mind? Does it benefit a greater good? When scraping ethically, we're not only considering what's legal, but also what's right. Apify has a beautiful use case with Spotlight, where we find lost children by scraping personal data. We're really proud of it and firmly believe it passes the legitimate interest test and the vital interest and public interest tests of GDPR.

Once you're certain that you're not hurting anyone with your scraping, you should analyze which regulations apply to you. If you're a company in the EU, GDPR applies to you even if you want to scrape personal data of people somewhere else in the world. As an EU business, you must do your research. Sometimes it will be okay to move forward because of legitimate interest, but more often than not you will have to pass that personal data scraping project to your non-EU partners or competitors. On the other hand, if you're not an EU company, you don't do business in the EU, and you don't target people who are in the EU, you will likely face less stringent regulations regarding personal data scraping. Also make sure to check your local regulations, like the CCPA.

Finally, you should program your scrapers to collect as little personal data as possible and keep that data only temporarily, to honor the minimization principle. Making a database of people and their information (e.g. for lead generation) is a very difficult case in protected jurisdictions, whereas scraping people from Google Maps reviews to automatically identify fake reviews and then discarding the personal data could easily pass the legitimate interest test.

Meta v Social Data Trading

Meta Platforms, Inc. v. Social Data Trading Ltd.In late December 2021, Meta Platforms, Inc., sued Hong Kong-based Social Data Trading Ltd. for scraping Instagram and Facebook profile data. Meta's case is built on the allegation that Social Data Trading Ltd. circumvented Meta's blocking measures and thereby engaged in illegal hacking under Section 502 of California's Penal Code. Meta had blocked Social Data Trading accounts, but alleges that the defendant used "thousands of automated Instagram accounts to improperly collect and aggregate data". Although the case seemed poised to establish a new and useful precedent regarding the effect of using fake accounts on legality, no substantial decision has been made. Social Data Trading never responded to the claim, leading the court to only issue a default judgment. This is an automatic judgment in favor of the claimant when the defendant fails to communicate with the court, despite being made aware of the proceedings.

Is scraping copyrighted content legal?

There's a lot of content legally protected on the internet. Some things more obviously than others. Music, movies, photographs? Sure, protected. News articles, blog posts, social media posts, research papers? Also generally protected. Websites' HTML, databases' structure, images, logos, and digital graphics? All those things are usually protected by copyright. One of the things not protected by copyright are plain facts. But what does that mean for web scraping?

If a piece of content is copyrighted, it means, among other things, that you cannot make copies of it without the author's consent (license) or a legal permission. Since the very definition of scraping is copying of content, and you almost never have the author's explicit consent, the legal permissions are your best bet. As always, the laws around the world vary. We will only discuss EU and US regulations.

Data mining in the European Union

In the EU, the scraping of copyrighted content is permitted by Articles 3 and 4 of the Directive 2019/790 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market (DSM Directive). The DSM Directive permits text and data mining, which means:

any automated analytical technique aimed at analysing text and data in digital form in order to generate information which includes, but is not limited to, patterns, trends and correlations;

This is very important because it means that scraping of copyrighted content is only permitted for the purposes of generating information. For example, you can scrape a webpage to extract prices from it, or books for natural language analysis, but you cannot scrape news articles and then republish them on your own website.

There are more conditions that you need to meet before your scraping is permitted:

- Scrape only what you have lawful access to - publicly available data.

- For scientific research, you can freely scrape almost anything.

- For business, the content owner can opt out of scraping by expressly reserving that right in a machine-readable format.

Application of robots.txt

The DSM Directive does not go into detail on how the express reservation in a machine-readable format should look like, but the general assumption is that the website owner can use the Disallow command of the robots.txt standard or other similar means to express that reservation. If the URLs you want to scrape are disallowed, you should not scrape them. Otherwise, you risk infringing the owners' copyright.

Fair use in the United States

In the US, the scraping of copyrighted content can be permitted by the fair use doctrine. The rules are somewhat similar to the European ones, but they do not make a sharp distinction between scientific research and for-profit scraping. The fundamental case law for the application of fair use to scraping is the Authors Guild v. Google (Google Books case). In the Google Books case, the court found that making virtual copies of copyrighted content - whole books - was permitted under fair use.

In applying the fair use doctrine to your scraping, we recommend first checking if you meet those conditions:

- The original content is transformed in a meaningful way. For example, a webpage's HTML is transformed into a list of product names and prices. Do not republish original content.

- Do not create a competing product. Scraping real estate offers for quantitative analysis is most likely ok. Scraping the same to publish them on your own website is most definitely not.

- If you can, do not copy a substantial portion of the original work. If you don't need certain data, don't scrape it.

Facts are not copyrightable, but watch out for database protection

It stems from the definition of copyright that facts cannot be protected because they are not an original work of an author but merely observations of reality. This was confirmed in C.B.C. Distribution and Marketing, Inc. v. Major League Baseball Advanced Media, L.P. What this means for scraping is that you mostly don't have to worry about copyright when you're scraping facts like stock prices or weather data in the US.

In the EU, things get a little more complicated. Under Directive 96/9/EC on the legal protection of databases (Database Directive), even facts can be protected if their collection, verification, or presentation required substantial investment. It means that if someone put a lot of effort into creating a collection of data, you can't just copy it and do whatever you want with it. Luckily, this limitation is overridden by the DSM Directive. So if you're scraping facts in the EU, make sure you meet the conditions listed above.

Ethical scrapers do not publish original works

Even though there are multiple ways to permissible scraping in the EU or the US, we would like to stress that the most important factor of all is to respect the original author's work and their business model. If you do that, there will hardly be any complaints from them. An ethical scraper does not re-publish or sell original works for its own profit. That's piracy, not scraping.

Scraping copyrighted content for the training of AI models

With AI being used so widely, an intriguing legal question has bubbled to the surface: Can you scrape and use copyrighted content for the purpose of training an AI model? As it stands, it's a bit of a mystery. Some experts are passionately arguing that it falls safely within permitted fair use, while others are equally insistent that it constitutes a sweeping infringement on copyright. The new EU AI Act, which came into force in 2024, puts in place rules for providers of AI models and is under criticism from both camps for introducing loopholes endangering copyright on one hand, but being unnecessarily strict on the other.

The courts are already buzzing with a few fascinating litigations on this topic.

In a 2025 landmark case, Bartz v. Anthropic, US courts introduced a crucial distinction regarding the source of copyrighted works that can be used for AI training. Training the Anthropic LLM on copyrighted books was deemed a “transformative” fair use, as the AI isn’t re-publishing the stories to compete with the authors, but instead analyzes them to learn the underlying patterns of human language. This legal protection, however, disappears when sourcing the training data from pirated “shadow libraries” such as LibGen. The court held that using an unauthorized digital copy is a standalone violation that isn’t excused by the transformative nature of the subsequent AI training.

This led to a historic $1.5 billion settlement, in which Anthropic agreed to compensate roughly 500,000 authors and destroy the pirated datasets.

For web scrapers, this case set a clear principle under the US copyright law: it is not just about what data you use for AI training, but where you get it from.

Notably, two headline-grabbing class actions led by Clarkson Law Firm against big players like OpenAI and Google. These cases aimed to represent millions of internet users and copyright holders alleging “illicit data collection”, misuse of “stolen information”, and dire warnings of AI spiraling into a “civilizational collapse”. The claimants tried to pull out all the stops, using every legal theory—even those that are only remotely applicable—to build their case. The extent of the claims and the number of legal theories they tried to apply underline just how uncertain they are and how unprepared the current legal landscape is.

Both cases were dismissed by federal judges in 2024 due to concerns over the breadth and vagueness of the complaints. The plaintiffs refiled their claims, and both proceedings are currently (as of early 2026) in the discovery phase. It is yet to be seen whether these amended filings will hold up, but what’s clear is that the courts will play a crucial role in shaping the emerging legal boundaries for generative AI.

Another lawsuit that's turning heads is the Getty Images action against Stability AI, currently unfolding in both the US and the UK. Getty alleges unlawful copying and processing of millions of images for training its AI art tool, Stable Diffusion. This case stands apart from the others because of the sheer volume of copyrighted material from the same right holder, as well as the significant role Getty Images’ data plays in the training materials of Stable Diffusion’s AI. Crucially for the tech industry, the UK court ruled in late 2025 that Stability AI’s model weights do not constitute “infringing copies” of Getty’s images, effectively legitimizing the core mechanics of AI training. However, Getty didn’t leave empty-handed: the court held Stability AI responsible for trademark violations where its tool generated blurred Getty watermarks. Meanwhile, the US side of the dispute has yet to be decided.

So, is AI-generated content protected by copyright law? And can copyrighted content be used to train AI? Check out our more detailed exploration of AI and copyright if you want to find out more.

Terms of Use and scraping

Can websites contractually limit scraping in their terms of use? Yes, they can. This may change in the future, but nothing currently prevents the website owner from adding provisions that ban scraping or automated access. But the real question is: Are those provisions enforceable? The legal theory behind contract enforceability is rather complex, but when talking about web scraping, the number one thing to check is the way how the contract was created.

What are browsewrap agreements?

Browsewrap agreement is a term used to describe contracts that were concluded simply by visiting a website. The worst kinds of terms and conditions may be hidden in a footer or buried deep in dropdown menus. Luckily, legal theory generally does not accept agreements of this type as valid, because it's unlikely that the user even read the agreement and therefore could not agree with its terms. The key component is the presentation of the agreement to the user. If the website uses a pop-up window to show the agreement, or positions the link to the agreement in prominent places, even a browsewrap agreement could be enforceable. The related case law is nicely summarized on Wikipedia.

What are clickwrap agreements?

Clickwrap agreements require an action by the user. Those terms will not be concluded simply by browsing a website, but by clicking a button or ticking a checkbox. This type of agreement is extremely common in online stores and in sign-up forms where the user needs to tick a checkbox before proceeding, or where the "Next" button has a note that says "By continuing you agree to our Terms and Conditions". Clickwrap agreements are perfectly fine and fair contracts, and the courts will readily enforce them. As evidenced in the Ryanair v PR Aviation case.

DSM Directive and Terms of Use

Scrapers in the EU will have a slightly easier time now, thanks to the DSM Directive. As we mentioned above, data mining is allowed under certain conditions, and if the website owner wants to opt out of scraping, they need to do so in a machine-readable format. This brings added security to web scrapers because they don't need their legal department to find and review complex terms and conditions of the website. Their scrapers will do that automatically.

Simple framework to evaluate Terms of Use when scraping

Even though the theory and case law might seem complex, in reality, it's quite easy to determine whether a website can successfully prevent scraping by its Terms of Use. When creating the scraper for a given website, pay special attention to the steps the robot takes through the website.

Does it at any point need to click a button that refers to the website's terms? Or does it need to close a modal with the terms to keep going? Is it performing a sign-up to some service? If the robot needs to perform a step that would bind a human to the website's terms, then it's very likely the terms were accepted lawfully and were binding.

On the other hand, if throughout the whole scraping flow you have not seen a single mention of the terms and conditions anywhere, they are probably buried somewhere deep, and it's probably not your job to go looking for them. If the website owners want the terms to be binding, they should display them prominently. It's only fair. Still, you should let your lawyers decide if you have any doubts.

This is a quote from the earlier-mentioned HiQ v LinkedIn preliminary injunction ruling. We feel it is a great guideline on how unilateral bans on scraping by the website owners should be approached:

[...] on balance, the public interest favors hiQ’s position. We agree with the district court that giving companies like LinkedIn free rein to decide, on any basis, who can collect and use data — data that the companies do not own, that they otherwise make publicly available to viewers, and that the companies themselves collect and use — risks the possible creation of information monopolies that would disserve the public interest.

CFAA and criminal liability in the US

There is one final issue that web scrapers in the US face. It is the extremely common claim that web scraping violates the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act - a controversial anti-hacking law enacted in 1986 (yes, that's before the modern Internet even existed). Under CFAA, accessing a computer system without authorization is a criminal offense. And courts have been arguing what "without authorization" means ever since.

The US Supreme Court has upheld a narrow interpretation of the law. In Van Buren v United States, the Supreme Court held that "the CFAA’s “exceeds authorized access” provision covers those who obtain information from computer networks or databases to which their computer access does not extend and does not cover those who, like Van Buren, have improper motives for obtaining information that is otherwise available to them."

The final answer to this legal question was delivered by the Ninth Circuit in April 2022 when it conclusively confirmed that scraping publicly available data is not capable of violating the CFAA. The Ninth Circuit built upon the case of Van Buren, where the US Supreme Court used the “gates-up-or-down inquiry” (i.e. if authorization is required and has been given, the gates are up; if authorization is required and has not been given, the gates are down) for access to a protected computer. In the newest HiQ v LinkedIn judgment, the Ninth Circuit pointed out that a defining feature of public websites is their lack of limitations on access; therefore - using the gate analogy - there were no gates to lift or lower in the first place. In other words, where there is no authorization required in the first place, there is nothing to withdraw from later. The CFAA concept of “without authorization” simply does not apply to public websites.

Large platforms' fight against web scraping

Meta Platforms, recently joined by X (Twitter), have taken a public stand against web scraping. To underscore their commitment, they've launched several lawsuits against companies like Octopus Data, Inc., BrandTotal Ltd., Mr. Ekrem Ates, Social Data Trading Ltd. (as mentioned earlier), and most recently, Bright Data Ltd., all of whom are connected to various web scraping software or services. But has all this legal hustle and bustle led to any decisive court judgments?

Yes. While some cases were settled out of court (Octopus Data, Inc. and BrandTotal Ltd.), and others were ignored by the defendant, resulting in default judgment (Social Data Trading Ltd., and likely soon Mr. Ekrem Ates), the litigation against Bright Data Ltd. has come to a conclusion.

Meta v Bright Data

Meta Platforms, Inc. v. Bright Data Ltd.Meta lost its legal battle against Bright Data, which Meta had previously employed for data scraping, but then sued for scraping data from its platforms.

The court ruled that Meta failed to prove the company scraped non-public data - meaning data that’s not behind a log-in screen or that’s password-protected. Meta's evidence didn't sufficiently show that Bright Data's collection of Facebook or Instagram user data, which was publicly sold, involved unauthorized access or breached contract terms.

Meta argued that Bright Data had used tools to bypass access restrictions like CAPTCHAs, which proved Bright Data collected data “behind authentication barriers.”

The court disagreed, stating that using an automated program to bypass a CAPTCHA “is different from accessing a password-protected website.”

Meta subsequently dropped its lawsuit against Bright Data, marking a notable defeat in its efforts to combat data scraping practices. The court's decision underscores the challenges in proving unauthorized data scraping and highlights the legal nuances of public versus private data collection.

Twitter, under its new guise of X Corp., has also recently jumped into the legal arena, suing unknown defendants for web scraping and alleging they taxed Twitter’s servers and breached terms of use. This legal effort ultimately failed when the court ruled that the company did not sufficiently prove direct harm or unjust enrichment resulting from the scraping of publicly available data.

Similarly to Meta, X sued BrightData for several claims, including breach of terms. The court dismissed X's claims related to scraping and selling information, ruling that such activities are permissible under copyright law.

Google v SerpApi

Google LLC v. SerpApi, LLCMost recently, Google’s 2025 lawsuit may provide clearer answers to web scraping questions that courts have so far only touched upon. Google accused SerpApi, a company providing developers with programmatic access to real-time search engine results, of bypassing technical safeguards and commercially exploiting Google’s search data. SerpApi argues that it merely processes information visible to any ordinary user, without bypassing authentication or retrieving non-public data.

Critics were quick to note the irony: Google’s stated mission is “to organize the world’s information” - a pursuit famously built on large-scale web crawling.

So, what's the takeaway from all this? At this point, it's hard to pin down anything concrete. Without any definitive judgments from these litigations, we can't really know whether the platforms' claims can be substantiated, whether the defendants breached the law, or if any damage was inflicted on the platforms. The only clear conclusion we can draw for now is that large platforms are none too pleased with web scraping.

Conclusion

So, is web scraping legal or not? Is data scraping legal? It's a complex problem, but we firmly believe that it is legal, and we hope this short and daringly simplified legal analysis convinced you as well. We also believe that web scraping has a great future ahead. We can see a slow but steady paradigm shift in the acceptance of scraping as a useful and ethical tool for gathering information and even creating new information on the internet.

In the end, it's nothing more than the automation of work routinely done by humans. Web scraping just makes the process faster and more reliable. Best of all, it allows people to focus on more important matters. Apify helps rescue trafficked children, find lost dogs and even restore forests with web scraping, so it can't be all bad, can it? 🙂

Further reading

If you still haven't had enough, here's a list of a few forward-looking texts that explain the topics we discussed in far more detail than we ever could in this article.

- AI and copyright: the legal landscape

- What is ethical web scraping and how do you do it?

- Are website terms of use enforceable?

- Making Room For Big Data: Web Scraping and an Affirmative Right to Access Publicly Available Information Online by Amber Zamora

- GitHub Copilot is not infringing your copyright by Julia Reda

- HiQ v LinkedIn disctrict court judgement

- HiQ v LinkedIn appellate court judgement

- HiQ v LinkedIn United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmation of district court judgement

- Web scraping case law: Van Buren v. United States

Get the latest updates and posts