Some websites include a prohibition of web scraping in their Terms of Use (“Terms”). Does that mean you have to find and read all the Terms before scraping any website? Not necessarily.

The Terms and any prohibitions they may contain have a legally binding effect on you only if they meet the standards of a valid contract. The legal analysis below aims to summarize when the Terms are binding and when not, according to US case law to date.

The 4 terms of use categories according to law

Since Terms must constitute a valid contract to be legally binding, their enforceability lies in the very basics of contract law. For a contract to be created, there must be an offer on the one side and an acceptance on the other.

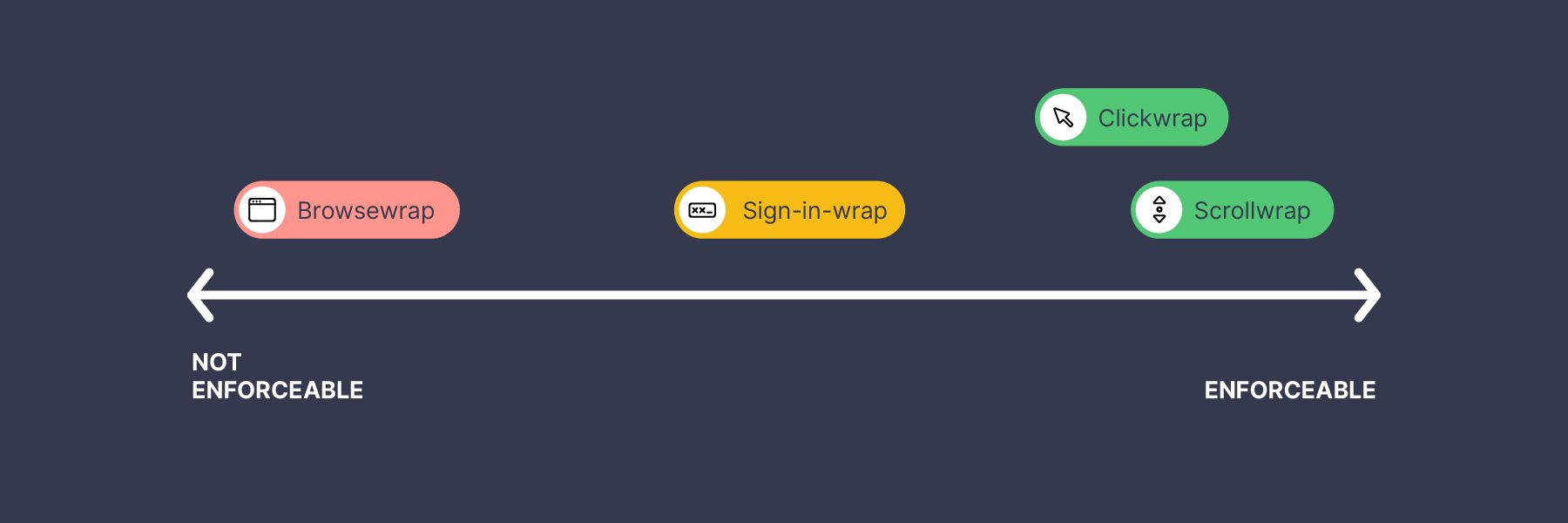

Terms are a type of adhesion contract (= non-negotiable contract presented by one party to another) which requires a slightly different approach when considering its creation than a traditional negotiated hard-copy contract. For contracts that are concluded on the internet, the theory and case law established the following categories to help with assessing their enforceability: “browsewrap”, “clickwrap”, “scrollwrap”, and “sign-in-wrap”.

Notwithstanding the category, the following general principles emerged from the case law:

- Terms will not be enforced where there is no evidence that the website user had notice of the agreement;

- Terms will be enforced when a user is encouraged by the design and content of the website and the agreement's webpage to examine the terms clearly available through hyperlinkage;

- Terms will not be enforced where the link to a website's terms is buried at the bottom of a webpage or tucked away in obscure corners of the website where users are unlikely to see it. [1]

What are browsewrap agreements and are they enforceable?

Terms are considered browsewrap agreements if they are posted on a website, typically via a link at the bottom of the page. The users are not required to expressly consent to them before using the website. The Terms instead state that by simply using the website, the user is agreeing to the Terms. The courts are traditionally reluctant to enforce browsewrap agreements, finding that the users could not have had reasonable notice of these Terms. [2]

That being said, browsewrap agreements can be enforceable provided that the users are given reasonable notice of the terms and exhibit unambiguous assent to them (which is however rarely the case). An example of reasonable notice may be placing the Terms in a prominent position on the home page (visible without scrolling to the bottom of the page), warning that proceeding further binds the user to the Terms, as was determined in the Register.com case. [3]

How extraordinary it is to find an enforceable browsewrap agreement can be demonstrated by statistical data: of all online agreements brought before US courts in 2021 only 8% were browsewrap agreements and none of them were upheld by the courts. In comparison the success rate of clickwrap agreements (including scrollwrap) before courts is 75%, while the success rate of sign-in-wrap agreements is 63%. [4]

Are clickwrap agreements enforceable?

Terms are considered clickwrap agreements where the user is required to take an action by which he confirms the consent to the Terms (typically via a tick-in box or “I agree” button). Courts in general find them enforceable. However even among them there are differences based on the way the Terms are presented to the user and the action that is supposed to constitute the assent.

The difference can be seen in the following examples. In the case of i.LAN Systems [5] the court confirmed that a contract is formed when the user clicks on a box stating “I Accept”. In the Sgouros case, [6] the court found a clickwrap agreement to be not binding because the website did not make explicitly clear that the button marked “I Accept” indicated assent to the Terms. The Terms were presented in a scrollable window at the top of the webpage, then other text followed that requested separate authorization, and only after that the “I Accept” button appeared.

How do scrollwrap agreements differ from other contracts?

Sometimes seen as a sub-category of clickwrap, a scrollwrap agreement requires the users, in addition to clicking on the “I Agree” button, to scroll through the text of the Terms (usually shown in a pop-up window) before they get to the “I Agree” button. Scrollwrap proves to be the most effective, leaving little room for doubt as to whether the user has been made aware of the Terms and assented to them.

See Moore v. Microsoft Corporation [7] maintaining that Terms were binding where the whole text was prominently displayed on the user's computer screen before the software could be installed and the user was required to indicate assent to the Terms by clicking on the "I Agree” icon before proceeding with the download of the software.

What are sign-in-wrap agreements?

Sign-in-wrap agreements are a hybrid of browsewrap and clickwrap. The act of acceptance here is the signing in or logging in with a note stating that by doing so, you are agreeing to the Terms. Instead of having a separate tick-in box or agree button for demonstrating the consent itself, the consent is bundled with the action of signing in. The case law view on enforceability varies: some tend to side in favor of enforceability, [8] some against. [9] The differentiating factor is purely factual and depends on the interface on which the Terms appear. [10]

The four “wrap” categories can be displayed on a spectrum of enforceability as follows. [11] Sign-in-wraps' precise location on the spectrum will vary from case to case.

Finally, it is worth noting that even where a contract is deemed to have been validly formed, a court may deny enforcement of it or of particular provisions that it deems unconscionable. This rule ensures that the more powerful party cannot ‘surprise’ the other party with some overly oppressive term. [12]

Endnotes

[1] Berkson v. Gogo LLC, 97 F. Supp. 3d 359 (E.D.N.Y. 2015).

[2] E.g. Hines v. Overstock.com, Inc., 668 F.Supp.2d 362, 365 (E.D.N.Y.2009); In re Zappos.com, Inc., Customer Data Breach Sec. Litig., 893 F.Supp.2d 1058, 1064–65 (D.Nev.2012); Edme v. Internet Brands, Inc., 968 F.Supp.2d 519, 525–26 (E.D.N.Y.2013).

[3] Register.com, Inc. v. Verio, Inc., 126 F. Supp. 2d 238 (S.D.N.Y. 2000).

[4] Ironclad 2022 Report “Clickwrap Litigation Trends” available through https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=9c510d59-bab9-44ed-8d62-dca2b3c21bcc

[5] i.Lan Systems, Inc. v. Netscout Serv. Level Corp., 183 F.Supp.2d 328, 338–39 (D.Mass.2002).

[6] Sgouros v. TransUnion Corp., No. 14 C 1850, 2015 WL 507584.

[7] Moore v. Microsoft Corp., 293 A.D.2d 587, 741 N.Y.S.2d 91, 92 (2d Dep't 2002).

[8] Fteja v. Facebook, Inc., 841 F.Supp.2d 829 (S.D.N.Y.2012).

[9] Sarchi v. Uber Technologies, Inc., 2022 ME 8; or Specht v. Netscape Communications Corp., 306 F.3d 17, (2d Cir. 2002).

[10] In re Facebook Biometric Info. Priv. Litig., 185 F. Supp. 3d 1155, 1165 (N.D. Cal. 2016).

[11] Ibid.

[12] Brower v. Gateway 2000, Inc., 246 A.D.2d 246, 253, 676 N.Y.S.2d 569 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1998), citing State v. Avco Financial Service, 50 N.Y.2d 383, 389–90, 429 N.Y.S.2d 181 (1980).